“At the opening of the fight, General Mead was with General Sickles discussing the feasibility of moving the Third Corps back to the line originally assigned for it, but the discussion was cut short by the opening of the Confederate battle. If that opening had been delayed thirty or forty minutes the corps would have been drawn back to the general line, and my first deployment would have enveloped Little Round Top and carried it before it could have been strongly manned.”[2]

Longstreet states his grievances with the attack on the second day in his memoirs but many historians find them to be unreliable because of his own bias and attempt to clear his name. Edward Porter Alexander blames Lee for allowing the delays to take place and states that an earlier attack on the Round Tops would have ensured victory, writing, “But it seems to me that while he might blame himself for it, general criticism must be modified by the fact that Gen. Lee’s granting the request justified it as apparently prudent, at the time.”[3] Others may say that a general asking for a delay for the well-being of his own troops is the sign of a caring commander, but Longstreet was against this from the beginning. If anything, on the second day of battle, he was delaying in hopes that Lee would change his mind; but what was going on with Ewell at this point was a completely different situation than what he was in on the first day.

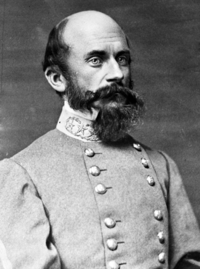

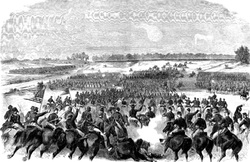

The largest fear of the Confederate Second Corps was whether or not the Union was digging in on Culp’s Hill and if they were, how well were they digging? They “…were turning their positions into even more defensible ones. They hacked at trees, gathered pieces of cordwood, rolled rocks around, and shoveled dirt, constructing the most formidable breast-works on the field at Gettysburg.”[4] Wadsworth’s shattered division, including the Iron Brigade, was facing the north of the hill with much of the Eleventh Corps facing the eastern side of the hill against the enemy. The Eleventh Corps had replaced the Twelfth Corps early on the evening, which was a great mistake for the Union as the men from the Eleventh had been heavily engaged on the first day of battle. “Yet the removal of most of the 12th Corps from Culp’s Hill during the early evening has been called a more serious error,”[5] than Sickles’ Salient. But what was even more dangerous to the whole situation, especially the Confederacy, was that Ewell did not begin his infantry attacks until 7 p.m. What was strange was that Ewell was supposed to begin his attack as soon as Longstreet’s guns could be heard, but what ensued was a fight in between the artillery: “Instead of making a quick assault – which would have complied with Lee’s orders and held the Federal infantry in place – he undertook a sustained bombardment, allowed the Federal infantry to avoid him, and ended with most of his artillery silenced and his gun crews crippled.”[6] While Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain was holding the south of the line, General George S. Greene held the north of the line at Culp’s Hill. He was the general responsible for the building of entrenchment and the fight in this area: “For three hours that night, the fate of the battle and possibly the destiny of the Federal cause hung on the staunch shoulders of “Old Pop” Greene, whose sturdiness had much to do with saving the hill for the Federals when its loss would have been calamitous.”[7] Had George Greene not been there, the hill may not have been held and the Federal cause been lost. But had Ewell taken the hill on the first day, we would have never heard the words “if practicable” in the reports of these generals. The second day of battle had been a difficult one for both sides and there were heavy leadership losses to the Confederate army including the wounding of J.B. Hood and the mortal wounding of William Barksdale. But one thing remained certain amidst all the casualties, there would be a fight the next day.

Ewell knew that he would have to attempt to take the position on Culp’s Hill on the third day but he would need help after all of the casualties from the second day. He gained the men of Rodes’ division which was engaged at the Oak Ridge of the first day of battle; they were also part of the third corps. General Early, who was also present on the first day’s fight, was used to reinforce Ewell’s position. As far as the Union position goes, the only remaining brigade from the Twelfth Corps, which vacated the previous day to be replaced by the Eleventh Corps, was Greene’s brigade and Williams’ brigade and they had no intention of leaving. “The battle for Culp’s Hill resumed about 4:30 a.m. when Federal artillery opened on the Confederate positions…this was the first of the three phases of the fight on Culp’s Hill during July 3.”[8] The Federal position was well fortified from the previous days and even after all of the fighting on the second, they were full with ammunition; that would be their downfall later on in the morning. “Brigadier General George Greene’s men fired so rapidly their guns became fouled and their ammunition ran low.”[9] Thankfully, General Williams from the Twelfth Corps rotated the line and placed his men in front; Greene’s men rested and resupplied. But even resting was slim during this engagement. “Federal fire was incessant. One soldier from the 1st Maryland Battalion (CSA) recalled it this way: ‘The whole hillside seemed enveloped in a blaze.’”[10] Ewell’s men moved in very odd fashions and the divisions brought to him to reinforce seemed to do more harm than good. It seemed as though Rodes’ men moved very little during this day’s engagement but were engaged with the enemy firing up the hill. It was not long in the day until Ewell pulled his men back from their attacking position and the firing slowed to a close, never finishing completely until the battle’s completion. Longstreet praises Ewell for his lack of following orders, at least in the terms “if practicable” mean, by claiming his insubordination to be just against Lee to take Culp’s Hill on the first day.

“It is the custom of military service to accept instructions of a commander as orders, but when they are coupled with conditions that transfer the responsibility of battle and defeat to the subordinate, they are not orders, and General Ewell was justifiable in not making attack that his commander would not order ,and the censure of his failure is unjust and very ungenerous.”[11]

It is very unique in this age that another commander, amidst endless blame, would praise another that had completely failed in his objective which speaks volumes about Longstreet’s character.

Though Longstreet states that Ewell did the right thing by not attacking Culp’s Hill on the first of July, there is much blame that is not placed on Ewell that is placed on Longstreet. Throughout the entire campaign, the general that performs in the worst sense of the word is J.E.B. Stuart who as the eyes and ears of the army, failed to provide Lee with information about the battlefield by arriving late on the second day of battle. Longstreet delays his attacks on the second day of battle which is hindering to the strategy but Ewell’s operation at Culp’s Hill is damaging to say the least. If the hill had been taken while there was no Federal presence on there would have drastically changed the face of the battle and maybe even the war. At the time of the war, it would have been dangerous to blame Lee for the failures at Gettysburg even though Lee tried to resign after the campaign. As the reports began to come into the war department, many of the commanders and soldiers pointed their fingers at Longstreet who openly stated that he did not desire to attack the position. As the assault on the third of July with Pickett, Pettigrew, and Trimble’s division seemed grand on a Napoleonic scale and the devastating battles on the previous day, Culp’s Hill seemed less important than the rest of the battle and to this day, Ewell’s operations seem to be ignored. As it seems today, the terms that Lee had given Ewell on that first day would haunt him for the rest of his life and would constantly lead everyone to believe what would have happened if they had taken the hill on the first day. The two words “if practicable” ruined the Confederacy and Ewell’s reputation.

As the Army of Northern Virginia began their retreat back across the Potomac, General Lee had a strange encounter. There was a soldier, a strong anti-Confederate soldier, who was wounded during the battle and lay by the street. As Lee rode by him ordering his generals into retreat, he recognized him and he raised his head stretching out his arm saying “Hurrah for the Union!” Lee dismounted Traveler and looked at the man with a grave look of defeat; as if his whole military career had come crashing down but tended to the boy with care. He extended his hand and grasped his firmly. “My son, I hope you will soon be well,” Lee replied. He had been brought down by this campaign as all of the Confederacy had; the last thing he had on his mind at the time was who to place the blame.

[1] Bowden, Scott and Ward, Bill. “Last Chance for Victory: Robert E. Lee and the Gettysburg Campaign.” Pg. 262.

[2] Longstreet, James. “From Manassas to Appomattox.” Pg. 382.

[3] Alexander, Edward Porter. “Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander.” Pg. 278.

[4] Hall, Jeffery C. “The Stand: The U.S. Army at Gettysburg.” Pg. 149.

[5] Ibid. Pg. 152.

[6] Tucker, Glenn. “High Tide at Gettysburg.” Pg. 301.

[7] Ibid. Pg. 302.

[8] Gottfried, Bradley M. “The Maps of Gettysburg: An Atlas of the Gettysburg Campaign, June 3 – July 13, 1863.” Pg. 242.

[9] Ibid. Pg. 244.

[10] Ibid. Pg. 244.

[11] Longstreet, James. “From Manassas to Appomattox.” Pg. 381.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed