Though the order from Lee to Ewell concerning Culp’s Hill is not in writing, it does appear in Lee’s report of the battle: “General Ewell was therefore instructed to carry the hill occupied by the enemy if he found it practicable, but to avoid a general engagement until the arrival of the other divisions of the army which were ordered to hasten forward.”[1] Taking that order too seriously may have foreshadowed the Confederate defeat at the onset of the battle. Many historians have stipulated whether or not Lee’s fight was set to be a failure from the beginning due to his numbers. With the Union army at an approximate strength of ninety-thousand men and the Confederate force sitting at seventy-five thousand, the idea of a surrounding strategy did not look well on paper. The first day’s fight was a struggle for the town but what was not seen was the exterior lines Lee would be forced to take south of the town. As the Union fishhook[2] was created and placed in effect, the battle seemed to play out immediately in favor of the Union. Longstreet noticed this right away on the morning of the second. “As soon as it was light enough to see, however, the enemy was found in position on his formidable heights awaiting us.”[3] He clearly noticed even though they had taken the town the previous day, all of the heights south had been taken by the Federals with their position dug in overnight. Not only had Culp’s Hill been taken, which Ewell had failed to attack on July 1st, East Cemetery Hill, Cemetery Ridge and Little Round Top were already in Union hands. On Culp’s Hill the Federal line was held by Slocum’s Twelfth Corps of just under ten thousand men; accompanying them was Wadsworth’s shattered division which was heavily engaged on the morning of the 1st.[4] To the south of the fishhook was the Fifth Corps holding Little Round Top with fourteen thousand men. So with the Union’s strong position, how would Lee’s force act against this? His own information was hindered because General J.E.B. Stuart had failed to retrieve information about the enemy’s position; in fact he was missing altogether. Lee would have to depend on cartographers and spies for his information which would cost him dearly: “Lee had wanted an early attack, but it was 11:00 a.m. before his order were issued…he moved on strange ground, his lead units taking heavy casualties from the sharpshooters of the Third Corps.”[5]

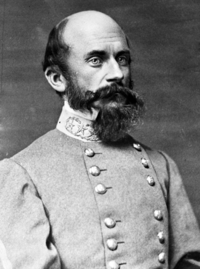

So why was Richard Ewell cautious of moving against the Federal position at Culp’s Hill? It was not as if he was a poor commander while under Jackson: “Ewell proved to be a skillful and successful division commander, and unlike Ambrose P. Hill and others, he was able to get along with Stonewall Jackson.”[6] What was interesting about Ewell is not his commanding abilities, but his eccentricities, “…he had a lisp that gave an added dimension to his pungent comments and to the blistering profanity he used when irritated.”[7] Placing aside any of his traits, personal and emotional, many men admired him for his closeness with Jackson and not because of his command abilities:

“Dick Ewell inspired men in spite of, not because of, his appearance…he had a fringe of brown hair on an otherwise bald and bomb-shaped head. Bright bulging eyes protrude above a prominent nose, creating an effect which many likened to a bird – an eagle, some said, or a woodcock – especially when he left his head droop toward one shoulder, as he often did, and uttered strange speeches in his shrill, twittering lisp.”[8]

Officers from Jackson’s staff stayed on, including the irreplaceable Sandy Pendleton. But what some of his subalterns began to wonder was whether or not he had the fury of Jackson, something that would not be seen on the fields of Gettysburg.

[1] Lee, Robert E. “The Wartime Papers of Robert E. Lee.” Pg. 576.

[2] See Appendix A.

[3] Longstreet, James. “From Manassas to Appomattox.” Pg. 363.

[4] See Appendix A.

[5] West Point Atlas of the Civil War. Pg. 84.

[6] Phanz, Harry. “Culp’s and Cemetery Hill.” Pg. 2.

[7] Ibid. 2.

[8] Tagg, Larry. “The Generals of Gettysburg.” Pg. 251.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed