Longstreet could easily see the issues of the proposed tactics as soon as Lee spoke them. He saw Gettysburg as a reversed version of Fredericksburg where instead of his men being well dug in, it was the Federals. The only thing he would need to turn the tide would be Big Round Top. Lee had wondered if a move that far south would seem as a retreating position to the enemy which they would take advantage of. But the term “if practicable” still swirled around the head of Ewell and Culp’s Hill lay in the hands of the Union. Ewell’s reasoning behind not attacking Culp’s Hill on the first day of battle was that most of his men were scattered through the town forcing the Federals back and as Lee had not wanted a general engagement, he abandoned the idea. Ewell would say, “I could not bring artillery to bear on it, and all the troops with me were jaded by twelve hours’ marching and fighting, and I was notified that General Johnson’s division (the only one of my corps that had not been engaged) was close to the town.”[3] Cautious as he may have been and due to the lack of troops, there were many commanders willing to aid in the capturing of the hill.

The terms “if practicable” ruined the Confederacy at Gettysburg and may have well ruined them for the whole war. Ewell’s confusion on the subject caused engagements on that hill both the second and third day of battle, which resulted in many violent actions and encounters. General Issac Trimble, though part of the Third Corps, was at Ewell’s side for the first day of battle, experienced the inability of command on Ewell’s part: “Trimble’s close association with Ewell ended after a stormy meeting in the late afternoon…[he] buzzed excitetdly, ‘General, don’t you intend to pursue our sweep and push the enemy vigorously?’…Ewell only paced about, cited Lee’s order not to bring on a general engagement, and looked confused.”[4] Trimble then began to argue with the commander asking for a division to take the hill which Ewell declined. He then asked for a brigade which Ewell also declined and in one last fit of energy, he asked for a regiment but Ewell snapped back. “‘When I need advice from a junior officer I generally ask for it.’ Trimble warned Ewell that he would regret not following his suggestions for as long as he lived, threw down his sword, and stormed off, saying he would no longer serve under such an officer.”[5] With the opportunity open, Ewell was concerned about the execution of his own orders; if he underestimated the Union’s force, he would pay for it greatly with many lives and failure. But any officer, or any soldier for that matter, could see the enemy was badly damaged on the first day’s fight: “At that time no fresh Federal forces had arrived to support troops so shattered that even the famous Iron Brigade, which had started the day happily against Archer, was never again to be effective as a unit.”[6] It seemed as though it was general knowledge the Union forces were weak at the time with no sign of reinforcements and still Ewell held back. In his report he does state the Union army showed a good fight while occupying Cemetery Hill: “The enemy had fallen back to a commanding position known as Cemetery Hill, south of Gettysburg, and quickly showed a formidable front there.”[7] His own account of the late afternoon and early evening of the 1st show no signs of the argument with Trimble nor does he mention the struggle with himself against the practicality of Culp’s Hill but conducted some scouting, nonetheless, before reporting to General Lee: “I represented to the commanding general that the hill above referred to was unoccupied by the enemy, as reported by Lieutenants Turner and Early, who had gone upon it, and that it commanded their position and made it untenable so far as I could judge.”[8] Upon that judgment, Lee allowed him to remain in his position and await orders. Many officers serving under Ewell would regret the day they did not take the hill as the Union was heard digging in that night.

Longstreet wanted to hold an attack, if not attack at all: “Longstreet wasted little time before restating his ‘views against making an attack.’…in Longstreet’s words ‘make a reconnaissance of the ground in his front, with a view of making the main attack on his left.’”[9] It would be in the Confederacy’s best interest that Big Round Top be taken for the high ground. That was, of course, if General Lee saw it as well. He had proposed the plan to take his corps to the south of the line and to attack Little Round Top while holding the larger hill; Lee took the plan into consideration and asked for opinions around command. The two commanders also noted that a southern movement that drastic could be seen as a retreating motion to which Lee was against. Attempting to find a plan that would completely work was difficult, however, and the two generals could not find a solid agreement to stand on. “He [Lee] gave Longstreet an outright order to place McLaw’s and Hood’s divisions on the right of Hill ‘partially enveloping the enemy’s left, which he was to drive in.’”[10] Longstreet, knowing that McLaw’s division was not fully present on the field at approximately 11:00 a.m., asked for a delay in attack which was granted by Lee. This was all, of course, before Sickles collapsed the Union line with his infamous salient. As Longstreet’s corps began their movements towards the positions for attack, many of the men seemed confused by what was going on; Longstreet himself riding far from the center of attention behind Hood.

[1] Ibid, Pg. 203.

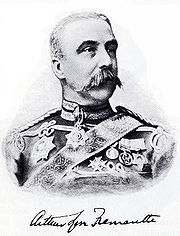

[2] Fremantle, Lt. Col. Arthur J. L. “Three Months in the Southern States: April – June, 1863.” Pg. 237.

[3] Ewell, Richard. “Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Union and Confederate Armies. Series I. Volume 27, Part II.” Pg. 445.

[4] Tagg, Larry. “The Generals at Gettysburg.” Pg. 329.

[5] Ibid. 329.

[6] Dowdey, Clifford. “Death of a Nation.” Pg. 145.

[7] Ewell, Richard. “Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Union and Confederate Armies. Series I. Volume 27, Part II.” Pg. 445.

[8] Ibid. Pg. 446.

[9] Trudeau, Noah Andre. “Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage.” Pg. 279.

[10] Coddington, Edwin, B. “The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command.” Pg. 378.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed